RITSEC CTF 2023 - Gauntlet write-up

This year is my first take on RITSEC CTF. Members of my team solved most of the challenges. I only solved one reversing challenge, Gauntlet, because it is particularly interesting to me. This post will also be my first public write-up after a long time.

Survey

Gauntlet - 250 points

Four parts of a key are being assembled within this file. The adversary has implemented four corresponding anti-debug checks that need to be bypassed. Good luck!

The challenge simply asks the player to bypass four anti-debugging mechanisms to receive the flag. It only provides a binary, which raises two questions:

- Where is the flag stored?

- Since there are anti-debugging mechanism, will the program print out the flag when running the challenge without debugger?

Considering the challenge description, it is likely the flag is stored in memory at runtime. As to whether it prints out flag when running without a debugger, sadly, that is not expected when we read the binary in decompiler.

When passing an anti-debug check, a part of the flag is copied into a specific buffer on stack (as if they were concatnated) and the program prints out a message that the mechanism has been bypassed. In case of failure, only the first two checks will inform so. The other two will silently skip the copying.

Attempt 1: Reversing string encryption

What if we extract the source string of those memcpy calls?

Turns out, this is possible, although not obvious.

Cutter/Rizin has the ability to demangle C++ symbol, and we were able to find

a symbol named ay::obfuscated_data.

Searching this online reveals a library the program likely uses to encrypt the

flag at compile-time and decrypt it at runtime:

adamyaxley:Obfuscate.

The library’s “Obfuscate” method is XOR-ing the data using 64-bit little-endian key.

Since template data is also stored in debug symbol, we can recover the initial template parameters: data size and key. We simply find XOR-encrypted data in binary and XOR again to reveal the unobfucated data.

For example, here we can find the encrypted string of the first part of the flag. (This was taken from Cutter decompiler - ghidra plugin)

iVar4 = FirstChallenge(char*, int*)::{lambda()#1}::operator()() const((int64_t)&var_21h);

*(undefined8 *)0x0 = ay::obfuscated_data<16ull, 3004872806184872195ull>::operator char*()(iVar4);

It looks ugly, but stay with me, this is just a normal day in C++. Here is how the

“compile-time encrypted string” library works at runtime.

First, the data is already encrypted at compile-time.

The lambda call in the first line abstracts the instantiation of ay::obfuscated_data,

decryption of the data, and store decrypted data at the memory which can be referred

through iVar4, which is likely an ay::obfuscated_data object.

The second line is just C-string casting call (i.e. (char*)s), likely used to access the underlying

decrypted data. We can confirm this by looking at the library source code

adamyaxley:Obfuscate/obfuscate.h#L205-L213

Now let’s try to decrypt data given the template above. We know 16 is the data size,

and the encryption key (according to the cipher function in library) is

03 69 E1 8F E5 73 B3 29. Now for the data, let’s inspect the lambda code.

In first few lines of assembly, it seems like we have found it:

mov byte [var_28h], 0x51

mov byte [var_27h], 0x3a

mov byte [var_26h], 0x9a

mov byte [var_25h], 0xde

mov byte [var_24h], 0x90

mov byte [var_23h], 0x1a

mov byte [var_22h], 0xd0

mov byte [var_21h], 0x42

mov byte [var_20h], 0x5c

mov byte [var_1fh], 0xa

mov byte [var_1eh], 0x89

mov byte [var_1dh], 0xea

mov byte [var_1ch], 0x86

mov byte [var_1bh], 0x18

mov byte [var_1ah], 0xec

mov byte [var_19h], 0x29

The number of line is 16, so it cannot be wrong. And with that, we found

the first part of the flag: RS{Quick_check_

Spending one hour on this to extract and concatnate data, I was able to extract

all instances of ay::obfuscated_data.

But when concanating, the output did not look like a flag at all.

It seems like there are additional conditions during copies.

Attempt 2: Binary patching

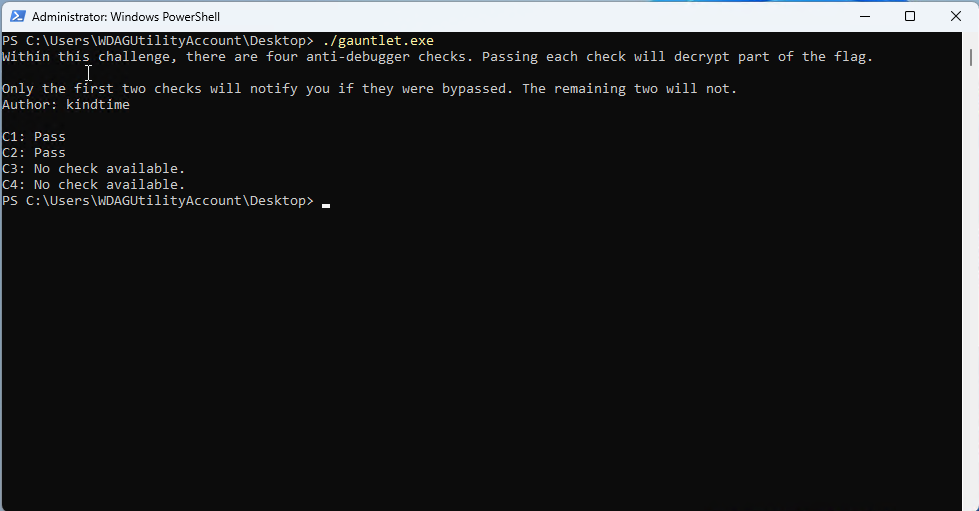

Instead of figuring out the conditions for individual copies of each part of the flag, I attempted to run the binary this time. Opening the binary in Windows Sandbox, the program only runs like what I expect from reading decompiled code in Cutter.

Looking at this, I suddenly had another idea. Since the buffer that stores flag

is on stack, which is predictable, can we modify the binary to print it out instead?

This idea came out partially due to the fact that I was revising for midterm

of one of my course. I didn’t find any integrity checking in the binary,

and anti-debugging mechanisms likely have nothing to do with binary integrity.

Additionally, the binary was statically compiled, meaning printf can be

easily referenced.

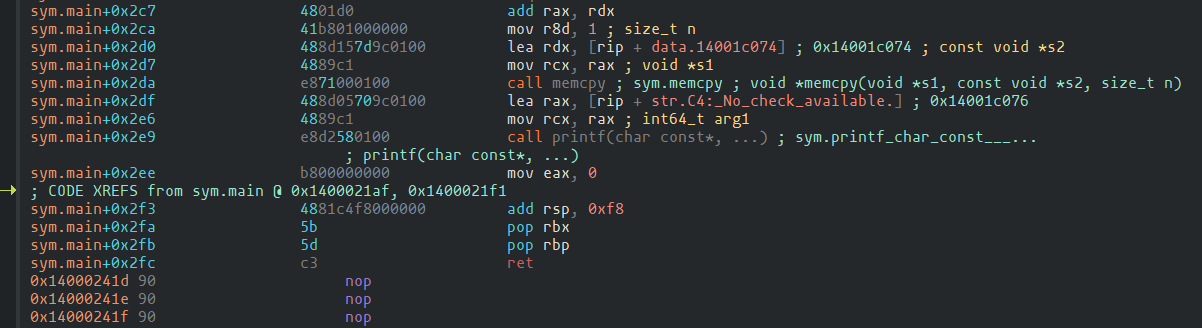

Luckily, we didn’t have to go far. After the forth part of the flag is copied,

before the end of the main function, I found a printf call printing out

“C4: No check available.\n”.

printf call receives the format string address stored in rcx register.

rcx is copied from rax, which in turn is computed by lea instruction.

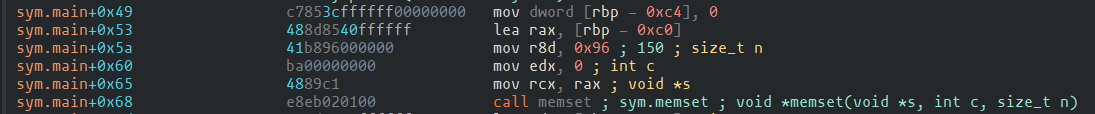

Meanwhile, thanks to the memset function call at the beginning of main function,

it is easily to calculate the offset of buffer that is suspected to be the flag:

rbp - 0xc0.

With that, we will change the last print call to use the address of the flag instead.

One way is to open Ghidra, click on the lea assembly line, right-click, and select Patch Instruction.

Then we can rewrite the instruction as we like and then export it.

The other way is to search for those assembly bytes in the hex dump and directly modify it. I chose the latter.

Old code:

$ cstool "x64" "48 8d 05 70 9c 01 00"

0 48 8d 05 70 9c 01 00 lea rax, [rip + 0x19c70]

New code:

$ kstool "x64" "lea rax, [rbp - 0xc0]"

lea rax, [rbp - 0xc0] = [ 48 8d 85 40 ff ff ff ]

When modifying binary, it is best not to change the size of the function. I used

Keystone engine to generate assembly, and luckily, the new code has a similar size of 7. (Although later I realized

there is a similar assembly line before memset call that I can just copy.)

Opening the binary in HxD, I searched for the targeted code bytes and replaced them.

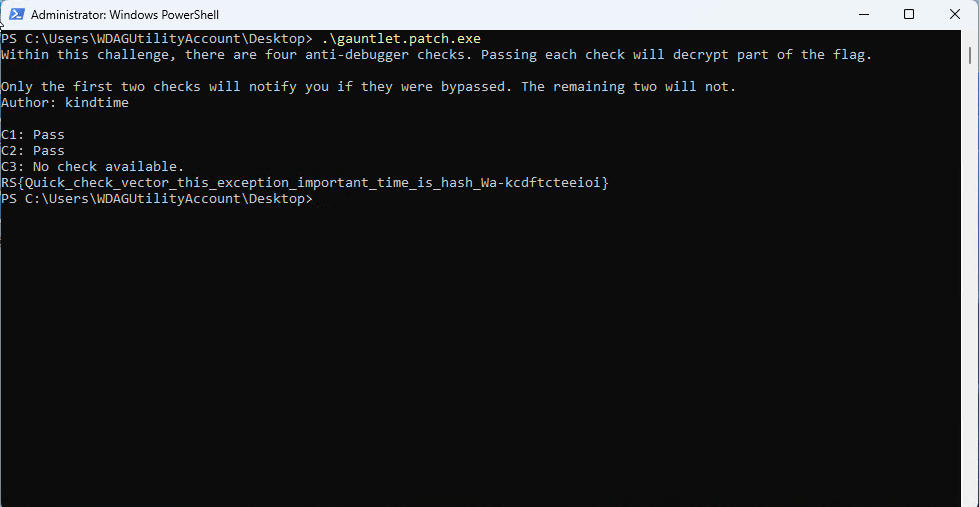

Then I copied the “patched” binary to the virtual machine to test it.

As expected, it prints out the flag without needing a debugger.

The flag:

RS{Quick_check_vector_this_exception_important_time_is_hash_Wa-kcdftcteeioi}

Conclusion

However, during the competition, it seems like the intended solution assumes the presence of a debugger, so the server flag was different from my submitted flag. According to the author’s fix note, the program can incorrectly generate the fourth part of the flag depending on the debugger in use. From my perspective, this issue remains even when the debugger does not exist, which makes no sense in terms of practicality. My flag was accepted anyway after the challenge was updated.

Overall, this is a fun challenge for me to learn the fact that static analysis can be greatly useful when dynamic analysis is difficult.